I am now going to post an Economic dissertation by a 20 year female Undergraduate – who has Zero interest in politics. It discusses fairly orthodox economic theory- but does so with out any links to the American Economy and thus it can be read by both sides with out worrying about being preached to. It is an interesting discussion about how to rebuild stagnant, one time Communist Eastern block Economies.

Stupidparty Clowns meet to rehearse their claptrap

Stupidparty Clowns meet to rehearse their claptrap

This post is asking a far simpler question. The point of this post is both to shed some light regarding orthodox economic policies, but more important to view this a juxtaposition to everything Sarah Palin and the other clowns stand for (i.e. gibberish) and ask who would make a better (though totally disinterested) President, a better ambassador for America – this 20 year undergraduate – or Sarah Palin and the rest of the Stupidparty Clowns.

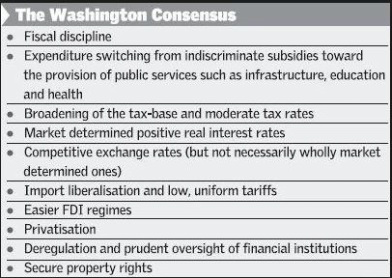

Just a Guideline, since consensus always evolving & never unanimous.

Just a Guideline, since consensus always evolving & never unanimous.

Introduction

By A. N. other Andendall.

The 1990’s was an enormously important era for democracy. While democratic ideals surpassed those of communism by the end of the Cold War, it was still unclear if communist countries could effectively transition to market economies. With the advantage of hindsight, we now have clearer insight than ever as to how Washington Consensus (WC) based polices played out in the transitioning world. As a general rule, countries that made a radical break from communism and best-employed liberalist strategies of transition wreaked the most benefits in the long run.

The Washington Consensus has a bit of an unfortunate label in that it has led some to believe it is a set of dictates imposed by the US on developing countries, which it is not. It is a completely voluntary ideal reform package with room for immense flexibility and varying degrees of liberalism that should be honed in to meet the needs of specific countries.

Consequently, it is hard to measure the exact success of the WC, especially because the WC itself is not a static concept. Still, because there is such a large pool of transitioning countries to observe, general trends can have valuable implications. The transitioning area is generally broken down into the Baltic, Central and Eastern European (CEE), South East Europe (SEE) and Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). CEE and Baltic countries consistently lead the charts in constitutional liberalism, real adjusted GDP, Human Development Index (HDI), transitional progress index, and other reform indicators. By looking at one of the most successful countries of the Former Soviet Union (FSU), Estonia, and one of the least successful, Belarus, we can identify some key differences in policy and gain insight of the source of their diverging paths. This comparative study, paired with an analysis of cross regional disparities, will suggest that the Washington Consensus does indeed provide sound economic advice.

The Washington Consensus is a dynamic concept that was continually tweaked and reassessed throughout the 90s, and so we must first qualify what we mean going forward by “Washington Consensus”. The WC was originally a set of ten specific policy points first introduced by British economist John Williamson. They were what he considered the optimal reform packages to be promoted by Washing based institutions, and included liberal reforms such as trade liberalization, deregulation, tax reform, and privatization. Birthed at the time of the Cold War, the WC became a sort of branding of Democracy.[1] The ten original policy prescriptions expanded to 20 by Washington based institutions such as the IMF as they were reassessed when further complications became apparent in transitioning countries.[2] In its most broad sense, mainstream WC ideology aligns with the three main pillars of transition to capitalism: liberalization, stabilization, and privatization. It also includes the development of some institutions, such as property rights, although it has been critiqued for downplaying this aspect. Additionally, it is generally paired with what is known as a “Big Bang” pace of reform. These will be the key liberal features of the WC analyzed in this paper. And, although the WC is intended to promote liberalism, it is important to note that the goal is to lessen the involvement of the state, but not to completely minimalize it.[3] The WC has often been misconstrued as a promotion of market fundamentalism. It is this version of the WC that often attracts the most criticism, and is irrelevant to this discussion.

For several reasons, it is difficult to measure how successful the Washington Consensus was. First, the Washington Consensus is adaptable and was shaped by the different economists who propagated it, thus it went through several different phases.[4] In fact, Williamson eventually published an “after Washington Consensus”, what he described as the result of “the natural historically evolutionary international development policy.” Second, countries incorporated these concepts to varying degrees, and thus there was no standardized application of the Washington Consensus across boarders.[5] Williamson himself states that it would be nonsensical for any country to follow these policy sets blindly; instead the WC should be honed in to meet the needs of specific countries[6]. Considering the WC itself is very ambiguous, to then measure how countries applied this set of policy ideals can be very arbitrary. Third, there are other extraneous factors that can effect how successful certain Washington Consensus based policies are. This includes factors such as time under Soviet Union rule, closeness to Western culture, and pre existing economic conditions.[7] This is a major limitation of both the WC and measuring its success. However, even with these uncertainties, existing literature and statistics include enough countries that strong correlations can be made between several key WC conditions and economic success.

Post-Communist Winners

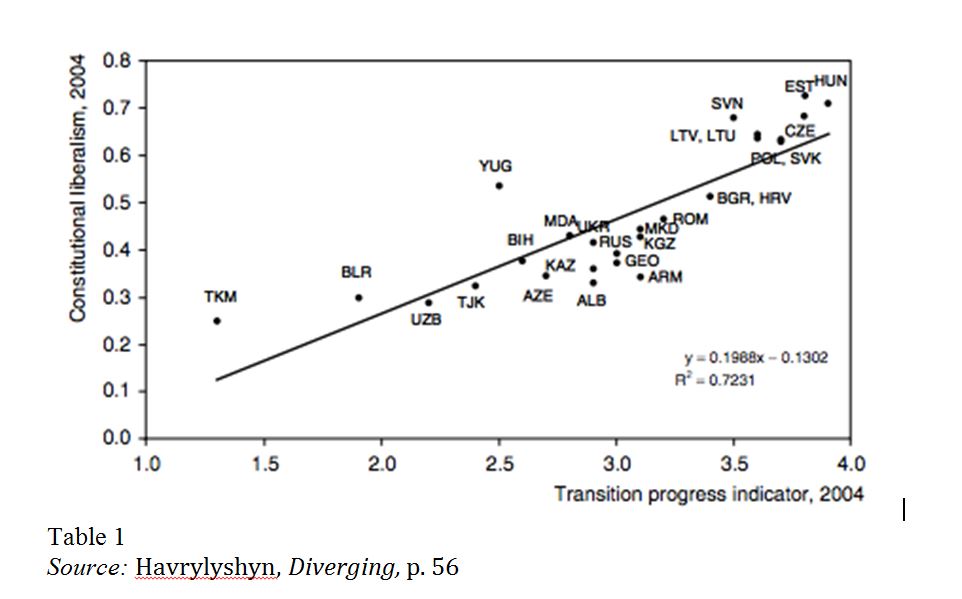

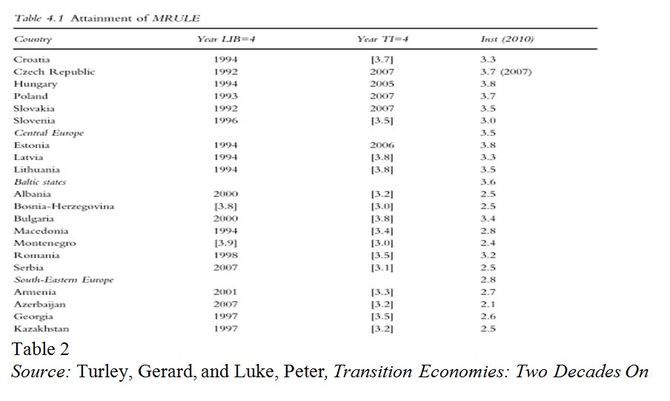

Consistencies amongst Post Communist Winners show the benefit of swift liberal reform as advised in the WC. While immediate policy liberalization imply heavy burdens of unemployment and poverty in the short run, it ultimately leads to greater market efficiency and growth in the long run. This is indicative of the “j-curve” style growth expected from “Big Bang” style reform. Today, CEE countries are the most affluent, have the least poverty and enjoy a more equal distribution of income than all other post communist countries. Furthermore, they attract the highest amount of foreign direct investment and spend a large chunk of their GDP on social welfare, both key pillars of the WC. It is thus unsurprising that they rank highest on the Human Development Index (HDI) and Real GDP levels.[8] CEE countries, followed by the Baltic countries, also rank highest on “liberalism” indicators such as media freedom and corruption index, evidence of a more thorough democratic process.[9] As illustrated in Table 2, constitutional liberalism and transition progress are highly correlated, with CEE and Baltic countries dominating the upper right corner.

The most successful post communist countries established the closest relations with the EU. These are the countries that were most open to radical change and benefited from European aid and monitoring, with the prospect of EU membership as the ultimate reward. The Acquis was the guide that provided the requirements a country needed to fulfill in legislation, intuitions, and procedures to join the EU, and was very similar in nature to the WC. In fact, part of the Acquis implicitly referenced the WC approach.[1] Thus, the act of accession to the EU can be seen as an indicator of political and economic reform that is very much reminiscent of what is encouraged by the WC. The biggest enlargement of the European Union was in 2004, where CEE and Baltic countries such as the Czech Republic, Hungary, Estonia Latvia, and Lithuania were included in the union.

Diverging Paths: Estonia and Belarus

For a more specific case study we will take a closer look at the diverging paths of two former Soviet Union countries, Estonia and Belarus. While most CEE and Baltic countries, including Estonia were radical reformers, in that they build democratic financial market economies that consisted largely of private ownership, Belarus maintained its old system of state control and predominant public ownership.[2] In 1990 per capita GDP of Belarus was 1,705 USD and of Estonia was 3,550 USD. By 2006, a couple years before the Euro crisis, Estonia’s per capita GDP had reached 12,340 USD while Belarus saw much less growth, with a per capita GDP of 3,550 USD.[3] By plugging these numbers into the percent change formula, we can calculate that from 1990- 2006, Estonia had a GDP per capita percentage change of 247.6, while Belarus had percentage change of only 123.5. Lets look first at the success story here, Estonia.

In many ways, Estonia got lucky with preexisting conditions that favored “Big Bang” style change, including a private sector that started to develop in the late 1980’s and culture that allowed a high level of willingness to change.[7] Estonia was ranked amongst the post communist countries with the strongest affiliation to Western cultural traditions. This preexisting condition is strongly correlated with successful transition.[8] Belarus did not have such luck with willingness to change, making processes such as privatization less lucrative, and highlighting limitations to the WC. One must be careful not to look at any one of the criteria of the WC in a vacuum, as the extraneous factors of each country will play a large part of shaping their outcome. Having said that, Estonia, a former Soviet Union state, still managed to pull out their deep roots in communism, and thus one must pay some tribute to their adoption of WC policies. As written by Economists Marek Dabrowski and Rafal Antczak in their article Economic Transition in Russia, the Ukraine, and Belarus in Comparative Perspective, “… the experience of the Baltic countries -especially of Estonia – shows that even the difficult Soviet heritage can be overcome, yielding more successful reforms than those in the three big Slavic successors of the USSR.”[9]

Belarus experienced a greater deal of resistance to political change, and thus economic markets remained dangerously reminiscent of that of the former communist regime. In terms of privatization, from 1992 to 1994 Belarus experienced only small-scale, experimental privatization efforts. By 1992, privately owned farms accounted for only 1% of agriculture.[10] Furthermore, Belarus failed to make radical reforms at the start of transition. Liberalization efforts were further hindered by the election of President Alexander Lukashenko in 1994, who made several efforts to reverse progress. For example, he lowered prices of consumer goods in his 1994 December Decree and consequently instigated serious food shortages by 1995. [11] Both failure to liberalize and continued state paternalism towards State Owned Enterprises s and agriculture are considered the two dominant factors that fed into Belarus’s struggle to stabilize their economy and the resulting intermittent threats of hyperinflation.[12] It is unsurprising that Belarus faced more painful transition costs than Estonia. Dabrowski and Antczak write of Belarus’s initial transition period; “the size of cumulative output decline was far bigger in the analyzed countries than in the Central European fast reformers and Estonia.”[13] Belarus’s inability to thoroughly break with its communist past resulted in a more painful transition process than Estonia experienced with its swift and radical reform.

Limitations

Two commonly argued limitations of the WC that go hand-in-hand are the heavy costs that swift and radical reform inflicts in the short term and the downplaying of the importance of preexisting institutions. When talking about short-term costs, it is inevitable that post communist countries will go through a recession, and this should not be considered evidence of faulty policy regimes. There are inherent costs of moving from a central to market economy and the initial impact of creating cheaper labor and harming local businesses are initial steps that can be very painful. When social costs appear at one time excessive decline in living standards and employment will inevitably test the strength of political support for reform. Yet, gradual reform allows time for resistance and is more susceptible to reversibility.[14]

Another major critique of the WC is that “Big Bang” style-reform doesn’t allow time for the appropriate development of institutions. Many of these critiques tend to come from economists that view the Washington Consensus in its most liberal, market fundamentalist sense, such as Stefan F. Stefanov critiques in article The Neo-Liberal Platform of the Transition to Market Economy-Specifics and Consequences”[15] However, even in its most mainstream understanding, the WC does not prioritize institution building above political and economic reforms. Nevertheless, discussing the technicality of whether the WC did or did not include adequate emphasis on institutions will not give us any more insight into the importance of preexisting conditions. As stated by economist Oleh Havrylyshyn, “debating whether the Washington Consensus road-map did or did not exclude institutions is not very useful.”[16] Instead, it is more interesting to try and gage the importance of preexisting institutions from the experience of transitioning economies.

Although gradualists stress the importance of establishing strong institutions before radical reform, proponents of Big Bang style reform believe that institution building will be a natural outcome of economic growth. Table 2 below shows that high scores on “early liberalization index”, “transitional index (TI)”, and institutional development, are all correlated.

While we hesitate to generalize from our results beyond the experience of transition, our article suggests that policy makers should not delay economic liberalization until changes in institutional infrastructure supporting markets have taken place. Instead, it appears that early progress in economic liberalization (even on more than political liberalization) has fed back into institutional change.[1]

Di Tommaso’s research on institutions aligns with the concept that early and radical reform is essential for long-term growth. However, it is still apparent from the country specific study above that there are other preexisting conditions besides institutions, such as Westernized culture, can make certain countries less viable a candidate from WC style reforms.

Conclusion

Belarus, as well as the other CIS countries, fell short when it came to economic reform. Unlike CEE and Baltic countries, Belarus did not make as immediate or radical a push towards liberalization, privatization and stabilization. Preexisting conditions, such as the presence of Western culture, likely hindered Belarus’s capability of implementing fast and thorough reform. Preexisting or extraneous factors like this should encourage us to refrain from pigeonholing reform advice into a static list of criteria, as politics, economics and culture are all inherently intertwined. It is important to see the WC from this perspective, and recognize its limitations at providing a universal set of reforms. Ideally the WC should provide a very broad framework that needs to be tailored to fit the needs of individual countries. For the WC to provide sound economic advice, the initial conditions and cultural and political framework need to be considered. The success of CEE and Baltic countries of meeting conditionality for EU accession reveals both an adherence to WC based economic reform and a certain level economic achievement. It is these countries, that have benefited more than any other post-communist countries in the long run, that implement the fast and sweeping liberal reform recommended by the most mainstream interpretations of the Washington Consensus.

References:

Anders, Aslund. 2008. ‘Transition Economies’. The Concise Encyclopedia Of Economics. Pennsylvania: Liberty Fund.

Coricelli, Fabrizio, and Nauro Campos. ‘Growth In Transition: What We Know, What We Don’t, And What We Should’. SSRN Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.314230.

Dabrowski, Marek, and Rafal Antczak. ‘Economic Transition In Russia, The Ukraine And Belarus In Comparative Perspective’. SSRN Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1476782.

Di Tommaso, Maria L., Martin Raiser, and Melvyn Weeks. 2007. ‘Home Grown Or Imported? Initial Conditions, External Anchors And The Determinants Of Institutional Reform In The Transition Economies’. Economic Journal 117 (520): 858-881. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0297.2007.02053.x.

Gillies, James, Jaak Leimann, and Rein Peterson. 2002. ‘Making A Successful Transition From A Command To A Market Economy: The Lessons From Estonia’. Corporate Governance 10 (3): 175-186. doi:10.1111/1467-8683.00282.

Havrylyshyn, Oleh. 2006. Divergent Paths In Post-Communist Transformation. Basingstoke [England]: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hellman, Joel S. 1998. ‘Winners Take All: The Politics Of Partial Reform In Postcommunist Transitions’. World Politics 50 (02): 203-234. doi:10.1017/s0043887100008091.

Katchanovski, Ivan. 2000. ‘Divergence In Growth In Post-Communist Countries’. Journal Of Public Policy 20 (1): 55-81. doi:10.1017/s0143814x00000751.

NaÃm, Moisés, and Moises Naim. 2000. ‘Washington Consensus Or Washington Confusion?’. Foreign Policy, no. 118: 86. doi:10.2307/1149672.

Turley, Gerard, and Peter J. J Luke. 2012. Transition Economics. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis.

Williamson, John. 1990. ‘What Washington Means By Policy Reform’. In Latin American Adjustment: How Much Has Happened?, 2nd ed., Chapter 2. Institute for International Economics.

Williamson, John. 2004. ‘The Washington Consensus As Policy Prescription For Development’. Presentation, World Bank.

World Bank Database

[1] Naim, Moises, Washington Consensus or Washington Confusion? Foreign Policy Magazine, 2000 (hereafter Naim, Washington), p. 88

[2] Williamson, John, The Washington Consensus as Policy Prescription, in Development Challenges in the 1990s: Leading Policymakers Speak from Experience, Besley, Tim, World Bank Publications, 2005, (Hereafter Williamson, Policy Prescription) Ch. 3

[3] Williamson, John, What Washington Means by Policy Reform, Chapter 2 from Latin American Adjustment: How Much Has Happened? Peterson Institute for International Economics, Washington D.C., 1990, (hereafter, Williamson, Washington)

[4] Naim, Washington, p. 88

[5] Naim, Washington, p. 88

[6] Williamson, Policy Prescription, p. 16

[7] Campos, Nauro and Coricelli, Fabrizio Growth in Transition: What We Know, What We Don’t, and What We Should, William Davidson Working Paper No. 470, 2002, p. 11 (hereafter Campos, Nauro Growth)

[8] Campos, Nauro Growth, p. 14

[9] Havrylyshyn, Oleh Diverging Economies: Capitalism for All or capitalism for the Few? Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2006, (hereafter Havrylyshyn, Diverging) p. 258

[10] Havrylyshyn, Diverging, p. 210

[11] Anders Åslund. “Transition Economies.” The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics. 2008. Library of Economics and Liberty. Retrieved January 8, 2015 from the World Wide Web: http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/TransitionEconomies.html

[12] World Bank

[13] Gillies, James, Leimann, Jaak, and Person, Rein, Making a Successful Transition from a Command to a Market Economy: the lessons from Estonia, Oxford, Blackwell Publishers Ltd, Vol. 10, No. 3, 2002, (hereafter Gillies, James Successful) p. 178

[14] Gillies, James Successful, p. 181

[15] Gillies, James Successful, p. 182

[16] Gillies, James Successful, p. 182

[17] Katchanovski, Ivan, Divergence in Growth in Post-Communist Countries, Cambridge University Press, United Kingdom, 2000, p. 71

[18] Dabrowski, Economic, p. 3

[19] Dabrowski, Marek and Antczak, Rafal, Economic Transition in Russia, the Ukraine, and Belarus in Comparative Perspective, Center for Social and Economic Research Warsaw, 1995, (Herafter, Dabrowski, Economic), p. 30

[20] Dabrowski, Economic, p. 16

[21] Dabrowski, Economic, p. 22

[22] Dabrowski, Economic, p. 38

[23] Hellman, Joel, Winners Take All: Politics of Partial Reform in Postcommunist Transitions, World Politics, vol. 50, No. 2, p. 215

[24] Stefanov, Stefan, The Neo-Liberal Platform of the Transition to Market Economies and Consequences, Economic Thought, Issue 7, 2004, pp. 24-43,

[25] Havrylyshyn, Diverging p. 38

[26]Di Tommaso, Maria, Raiser, Martin and Weeks, Melvyn Home Grown or Imported? Initial Conditions of External Anchors and the Determinants of Institutional Reform in the Transition Economies. The Economic Journal, 117, pp. 858-881, Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, 2007, p. 876

Leave a Reply